Toyota, Zara, and South Park: How to Find a Successful Business Model

What can and cannot be predicted in business? How can market share be increased regardless of high costs? Why is nanotechnology no guarantee of success? What can we learn from Edison, and what from the gnomes of South Park? Professor Serguei Netessine of INSEAD business school discussed these questions and more during a master class and the presentation of his new book at the Higher School of Economics.

About Serguei Netessine

Professor Netessine has been working in the U.S. and Western Europe for nearly 20 years. A graduate of the Moscow Institute of Electronic Technology, he set off for the U.S. in the mid-1990s to study management in the fields of science and business. In combining his technical background with his newly acquired management knowledge – Netessine holds a master’s and Ph.D. from the University of Rochester – he began conducting research on entrepreneurship, business processes and innovations. For nearly 10 years Professor Netessine taught at the Wharton School, and in 2010 he became a professor at INSEAD, heading the Wharton-INSEAD research alliance. In addition, Netessine is the director of Sberbank’s educational programme, which is a year-long programme of study that some 1,500 managers from the Russian bank have already completed.

Netessine was invited by the International Institute of Administration and Business to speak at the HSE, where he presented his latest book The Risk-Driven Business Model: Four Questions that will Define Your Company, written in collaboration with another INSEAD professor, Karan Girotra. In their book, Netessine and Girotra try to show how innovations in management can sometimes be more effective than innovations in production, and they did this not only in theory but by using concrete examples. The authors also posited that the future of companies does not depend on the implementation of nanotechnology, but on the quality of their business models. Why this is happening, Netessine discussed in his lecture.

We cannot predict which technologies will take off

The largest companies around the world are spending billions of dollars to finance their research and development divisions. As if by default, it is believed that the best way to become a leader on the market is by employing production innovations and by acquiring new items and technologies that the consumer will undoubtedly want to have in his or her possession. At the same time, business practice shows that there is no direct link between massive investments in ‘trendy’ technologies and consumer demand for them.

Forecasting the potential of new technologies is an entirely thankless task and few can boast of a good forecast ‘record’ in world of business. And this concerns both those who create overly optimistic forecasts, as well as the pessimists. Take, for example, the fact that leading scientists and businessmen once argued that humanity would never be able to use nuclear energy or that computers would never appear in homes.

Of course, everyone knows of successful examples of technological revolutions, but few know of the numerous failures that have taken place in history. How many people know, for example, that on the Newton project alone (a series of handheld computers produced in the 1990s), Apple lost two and a half billion dollars?

Another example of a failed technological miracle is the Segway, which is amusing and fully in line with a sci-fi version of a vehicle of the future. But Segway inventors and manufacturers missed the most important questions: exactly what does the Segway offer the consumer and under which conditions can he or she use this device? Is the Segway considered a car or is the driver still a ‘pedestrian?’ Where should it be ridden: on the sidewalk or in the road? Where should you park the Segway? How do you charge it? This uncertainty resulted in the Segway being banned on public roads in some countries.

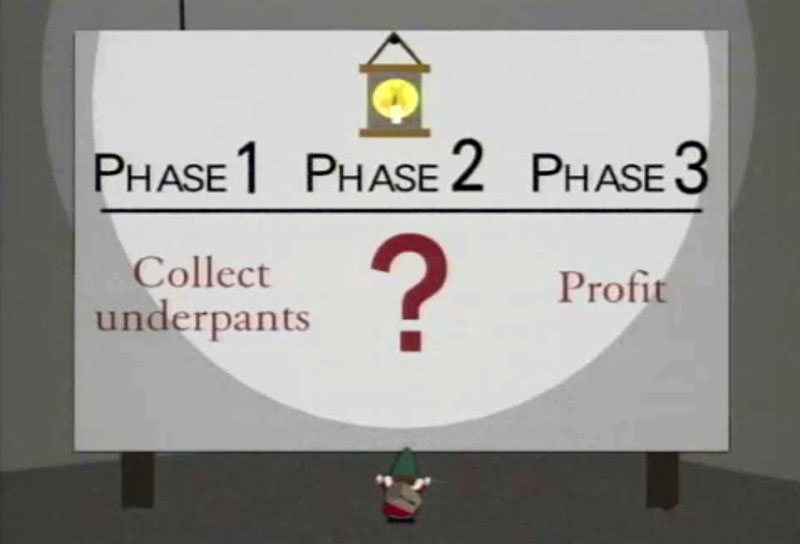

Why businessmen look like the gnomes of South Park

The creators of the cult cartoon series South Park succeeded most in using their standard satirical style to highlight the main flaw in contemporary business models. One episode shows how a group of gnomes sneaks into houses and steal underpants. When asked how their business plan is structured, the gnomes answered that the first phase is to collect underpants, then comes the second phase, which is followed by the third phase – collect profit.

The gnomes found it hard to say what was hidden behind the mysterious ‘second phase’ and specifically how they plan to raise profit from underpants. But set on success, they continue on with their ‘business,’ which is ingenious in its simplicity.

Edison, who invented more than the light bulb

One person who can be called a genius innovator is Thomas Edison, and not just because of the light bulb, the invention for which he best known. It was not enough to come up with a way to replace candles – what good is a light bulb without electricity or generating companies? Edison’s success lay specifically in the fact that he created an entire business model for power supply, a business model that provided a framework for all stages of the production and sale of electricity: power plants, distribution networks, electrical wiring in homes, etc.

So Edison's main innovation lies not in technology, but in economic and business known-how. The same can be said about the successes of Toyota, whose business model other automobile manufacturers try to copy. The essence of Toyota’s business model lies in the fact that it seems the company does not do anything in particular, but nonetheless yields a result. And when we come to think of it, Henry Ford’s conveyer-belt assembly line is actually the innovation of a business process; after all, cars did not change by themselves just because they were assembled differently.

The implementation of innovative business models is the path that many developing countries are taking and a path that Russia should also take. This could be where competitive advantage on the global market lies, as opposed to spending billions on technologies whose potential demand is not known.

Innovations that factor in risks

What exactly is a ‘business model?’ There are different definitions of the term, but, as a rule, the business model consists of three parts: the structure of revenues, the structure of expenses, and turnover. An attempt is also made to optimize the three. The problem, however, is that standard business models and forecasts are based on averaged data. But just like the average temperature in a hospital tells us very little about the status of specific patients, averaged calculations do not guarantee success in business.

An innovative approach should be taken not in planning revenues and expenses, but in factoring in the risks that businesses face. There are two main types of risk – informational and motivational – and a company will achieve the desired results by making provisions for them.

Offer the buyer what he wants when he wants it

While the majority of businessmen try to anticipate consumer attitude and tastes months and years in advance, some companies operate on the principle of ‘here and now,’ not relying on potential demand, but on real demand. Examples of such companies can be found in the computer market, for example Dell, which first receives money from the client and then delivers a finished computer, and the services market, like the LiveOps call centre, which has no permanent office, but a flexible staff of home-based telephone operators.

Perhaps the most striking example of such an innovation strategy is demonstrated by the company Zara. Unlike its competitors, Zara has not moved the production of its clothing and accessories to countries with cheap labour, but maintained production in Spain, a very expensive country in this regard. The company ships goods via airplane, which is also very costly. In addition, Zara does not spend money on advertising, instead investing in opening new stores. How is the company able to increase its market share?

Zara is constantly working with customers at its stores, determining their fashion preferences on a daily basis and immediately responding to customer requests. The company claims it can take a design from the drawing board to the store shelf in as little as two weeks. In this way, the stores themselves are Zara’s best form of advertising as they are constantly updating their selection. And its financial success is not even affected by high production costs.

Create stimuli for consumers

Many have probably come across ‘long-lasting’ light bulbs, which according to their manufacturers, save a significant amount of money. The problem is, these light bulbs are expensive and you would need to use them for a very long time to notice any savings. Too long for the consumer to see the benefit.

For many years Israeli company Netafim, a manufacturer of irrigation systems and equipment, faced a similar problem. Netafim’s products were indeed unique in their high quality, truly helping consumers achieve a much higher crop yield. The products were, however, too expensive for second-tier farmers to afford, especially poor farmers in the Middle East, as well Central and Southern Asia. Then Netafim improved technology and cut the price in half, but it was still too high.

Everything changed when Netafim thought up a new sales method: the farmer does not pay anything for the equipment or its installation, but at the end of the year crop revenues over the norm are divided equally between the farmer and Netafim. The farmer, in agreeing to such a deal, is at no risk: in the worst case, the farmer makes as much as he did before. Netafim’s new motivational approach worked, and the company began rapidly increasing sales, now holding 30% of the world market for irrigation equipment.

Why innovative business models cannot be copied

The majority of the recipes for success detailed above seem very simple, but they should not be employed blindly. This is not only because it is impossible to reproduce all of the conditions under which these models were effective. Even if you were able to reconstruct a successful business process, you would also be repeating the mistakes of the process that are unavoidable on the path to success.

Cautioning against copying, Serguei Netessine gives one more piece of advice from his personal experience: do not immediately reject an idea that at first glance seems banal. Netessine’s students told him many years ago that they wanted to begin selling diapers online. He did not take this idea seriously at first – who can compete with Amazon.com? But time went on, and Diapers.com had such good turnover that the magazine BusinessWeek released an article called, 'What Amazon Fears Most: Diapers.' And a little later, Amazon purchased its unexpected competitor for half a billion dollars.

Maybe the gnomes from South Park were really onto something?

Oleg Seregin, HSE News Portal

Photos by Mikhail Dmitriev

Oleg Seregin