Running at a Deficit: How the Lockdown Affected the Global Economy and What to Expect in the Short Term

Countries across the world announced support measures in the amount of USD 11 trillion to pull the economy out of the crisis caused by the pandemic and lockdown. Such hefty money injections into the economy will promote GDP recovery but at the same time may raise the spectre of growing public debt. Sergey Pukhov, the lead expert of HSE Centre of Development Institute, talked to the portal's News Service about the matter in question.

The global economy entered 2020 with a number of problems. The UK's exit from the European Union and re-examination of relations with the USA by a number of the largest countries – in particular, a non-declared trade war between the US and China – led to global trade slowing down by around 1% following 2019 results, despite its growth by almost 4% back in 2018. Uncertainties in trade relations were accompanied by a cooling of investment activity. All in all, global economic growth rates in 2019 fell below 3% in purchasing-power-parity (PPP) vs. 3.6% in 2018 and 3.9% in 2017.

That said, the global economy’s long-term prospects were not of great concern, and international financial organizations predicted that growth would quicken. However, China and other countries were forced to impose stringent lockdown measures against coronavirus early in 2020. Borders were closed, many production sites were shut down, international value-added chains were disrupted, but the most jeopardized industries turned out to be retail trade, tourism, entertainment and recreation.

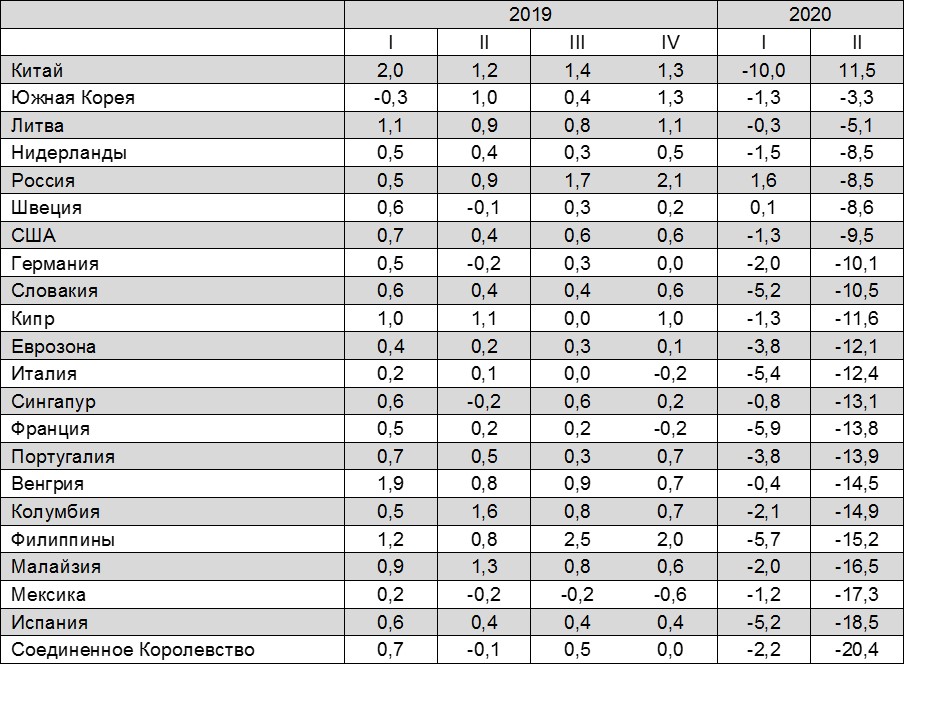

Following a slight decrease by 1.3% in Q1, US GDP dropped by almost 10% in Q2, primarily due to a dramatic reduction in people’s spending on services. Various enterprises were forced to go through massive downsizing, the number of bankruptcies was similar to the level during the 2008 crisis, and the unemployment rate reached Great Depression levels in 1929-1932. The eurozone economy collapsed even more—by more than 12% in Q2 after falling by 3.6% earlier in the year. The most dramatic GDP reduction was registered in Spain, Hungary, Portugal, and France, with the lowest one reported in Finland and Lithuania. The UK’s GDP fell by more than 20%, which turned out to be an all-time record among the world’s major economies. Compared to other countries, the UK postponed anti-virus measures longer and lifted them more slowly. The lockdown led to reduced output in all sectors apart from pharmaceuticals. The hotel industry, education, and catering services got hit the hardest. At the same time, following its decline by 10% in Q1 GDP, in China it grew by 11.5% in Q2 vs. Q1. This made it possible to win back the losses that took place at the beginning of the year, but not to exceed pre-crisis levels.

GDP in real terms subject to seasonal adjustment, % Q/Q

There are several key reasons for variance in the rate of decline in different countries. First, there was differing severity and duration of lockdown measures. Second, the extent of fiscal and credit support measures for the economy differed. Third, there are differences in economic structure. Countries where services made up the greatest share of the economy's structure suffered the most from the crisis. For example, the share of services is almost 82% in the UK, 81% in the USA and France, and 77% in Spain and Italy, whereas it is just over 53% in China and 64% in South Korea. Fourth, the quality of medical services differed. A dramatic incidence rate triggered a crisis in health care, and all resources were committed to overcoming it and increasing the number of available hospital beds and medical staff. A variety of protection measures against coronavirus were introduced depending on the state of the health care system and government funding. Some countries focused on voluntary use of personal protective equipment, while others adopted rigid quarantines and shutdowns of a number of service and production enterprises. The last factor is engagement in the global value-added chain. Decreased external demand, disrupted supplies due to enterprises being shut down, and trade limitations resulted in a decline in exports. This factor will constrain the economic recovery when the lockdown is lifted since exiting quarantine will occur at different times.

During a gradual easing of lockdown measures, which led to a rising incidence in recent months, the experience of "Covid dissidents", like Sweden, seems really interesting. Sweden’s GDP dropped by 8.6% in Q2, which was driven primarily by declining exports and household consumption expenditures. Sweden did not introduce stringent restrictions despite the spread of infection. Service-sector companies remained open, including cafés and restaurants, malls, schools, and kindergartens. Swedish officials opted to simply encourage their people to observe precautions, without mandatory wearing of masks in public places, and only around 20% of citizens wear them. Sweden ranks 24th globally in terms of the number of sick people, but in terms of the death toll, it takes 8th place after Italy, Great Britain, Spain, Chile, etc. Due to the lockdown, Sweden's GDP has dropped by less than in most European countries, the United States, Japan, and China; however, the question of whether the Swedish economy will recover faster than the other ones remains an open one.

In our opinion, given the adverse consequences for the economy and household income, lockdowns can be replaced by individual protection measures—the mass use of masks and gloves, and social distancing. The main problem is compliance with these measures. Major fines and penalties will promote compliance with requirements that will slow the spread of epidemics; however, as opposed to PPE use, it's difficult to ensure full-scale social distancing. For example, it will lead to fewer people in public transport, cinemas, and restaurants, which will be accompanied by a higher cost of services and lower demand.

According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the budgetary measures that have been unveiled to address the pandemic's adverse consequences in all countries are estimated at US$ 11 trillion. Half of these measures represent additional expenses and lost earnings. The other half is liquidity support in the form of loans, capital injections and guarantees, including those provided through state-owned banks and companies. These can lead to an increase in public debt and deficits down the road. All in all, fiscal support measures for developed countries amount up to approximately 20% of GDP, whereas in developing countries they are only 6% of GDP. The maximum support level was noted in Germany, Italy, and Japan, mainly in the form of loans, capital, and guarantees.

In the context of stringent lockdowns, budget revenues fell dramatically and measures to support taxpayers led to growing expenses. The IMF’s current projections show that the average global budget deficit is expected to rise to 14% of GDP in 2020. This is 10 p.p. higher than in 2019 and is primarily a response to Covid-19. The budget deficit of developed countries is expected to grow this year up to nearly 17% of GDP, or by 13 p.p., and in developing countries—up to 11% of GDP, or by almost 6 p.p. The United States, Germany, and Canada provided the greatest support to their economies. The United States, for instance, allocated a record-breaking amount of budget funds as part of their monetary policy (almost 12% of GDP) to support citizens and businesses. The maximum assistance among the developing economies was observed in Brazil (12%), South Africa (10%), and Russia (3%). As a result, the budget deficit in Brazil will grow by 10 p.p. up to 16% and in South Africa by 9 p.p. up to 15%; the 2019 net surplus in Russia (2%) will be replaced by a 5.4% deficit.

Although such hefty money injections into the economy will promote GDP recovery, there is a simultaneous threat of rising state debt. According to IMF forecasts, due to a sharp increase in the burden of public finances, 2020 global public debt will exceed 100% of GDP, growing by 19 p.p. over 2019. Once a safe and effective commercial vaccine is available, the economic situation will improve, less financial assistance will be required, and growth in national debt growth will decrease.

According to the IMF, stimulus spending in the United States will lead to an increase in government debt from 109% in 2019 up to 141% by the end of 2020. The maximum debt growth—by 31 p.p., up to 166% of GDP—is forecasted in Italy. Brazil is the only developing country where the debt burden will exceed GDP. In Russia, the public debt will remain at a safe level, below 20% of GDP, which is one of the lowest in the world.

As the lockdown has eased over the past several months, business activity is growing, production sites are being put back in operation, and services are resuming. In July, the composite purchasing managers' index (PMI), which describes the global situation with industries and services, was above the threshold level of 50% for the first time since this February, indicating the start of growth in global economic activity. In manufacturing, the leaders of growing business activity are car manufacturing, chemicals, pharmaceuticals, consumer goods, and construction materials; in the service sector, health care and banking are the leaders. The most significant recovery was observed in Australia, France, and the UK. The US also recorded growth below the global average. At the same time, activity continued to decline in India, Japan, and Brazil.

Although the survey data indicate resumed growth in business activity around the world, they show nothing about the pace of recovery. The current global index most likely indicates weak growth only of the global economy, but as the index approaches 60, business activity will grow significantly. This will be facilitated by large-scale measures involving budgetary incentives and monetary policy, assistance from international financial organizations, and automatic budget stabilizers in developed countries. Most countries are expected to resume economic growth in Q3.

The predictions by the international financial institutions published in June-July assumed a global economic slowdown this year of 3.5-6.0%

Rising incidence of coronavirus and another anti-epidemic lockdown remain the key risk factor. We do not believe an extremely strict lockdown will be re-imposed even with another outbreak of the disease. A lockdown does not come cheap for the global economy in general. However, social distancing requirements may be kept in place until a coronavirus vaccine is commercially released. It will certainly slow the recovery but will not stop it. According to IMF and World Bank forecasts, the growth of the world economy in 2021 will therefore fully compensate for the decline of this year. The ОECD forecast is more conservative and presumes that the economy will grow in 2021 by 5.2% following the 6% decline in 2020. In subsequent years, following the exhaustion of the low base effect, the growth rate will slow down, approaching the potential 3.5% per year. In any event, the forecasted trend of global economic growth in the medium term turns out to be lower than the pre-crisis one. To reach the pre-crisis trajectory by 2025, the world economy must grow by 5-6% per year, which is unlikely in the context of a trade war between the US and China, a higher debt burden of both developed and developing countries, and the need for fiscal consolidation. A higher debt burden on the economy could limit the scale and effectiveness of further budgetary support measures.